L

eaning forward in a wing chair upholstered in Belgian linen, at the head of the distressed pine dining table he uses as a desk, Gary Friedman, chief executive of furniture chain RH, swipes at an iPad in search of a video. Unsuccessful, he hollers to an assistant sitting outside his Corte Madera, California, office, which has no door. As she hunts, Friedman, 61, recalls telling employees at the April 2017 RH leadership conference where it was first shown, “We have to be willing to march through hell for a heavenly cause.” Found several minutes later, the clip, shot in moody black-and-white, shows employees staring defiantly into the camera, then cuts to a series of negative headlines. (“Is Restoration Hardware a Broken Stock?” asks one.) The soundtrack is Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song”—made famous during Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign—but Friedman has updated the lyrics to suit his situation. (“I’m kind of a little bit of a second coming of ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic,” he says, referring to the singer-songwriter known for his pop music parodies.) Here the chorus becomes, “This is our fight song, take back our brand song.”

In 2017, RH—which became Restoration Hardware’s moniker in 2012—was in deep trouble. A botched rollout of a new furniture line had cost millions in canceled orders and concessions, exposing severe problems in the company’s distribution systems. That February, the stock had slid to $24, down 77% from its November 2015 high. Two years later, Friedman believes he has staged the comeback his video promised, continuing his quest to shed Restoration Hardware’s reputation as a vendor of nostalgic reproductions and to reimagine it as a sumptuous home lifestyle brand.

(Clockwise from left) RH New York was once home to Pastis, a popular French bistro. In Chicago, RH renovated a 1914 dorm for women in the arts. And in West Palm Beach, RH commissioned a mural by graffiti artist RETNA.

Sales increased 14% in fiscal 2017 (which ended in February 2018) to $2.44 billion. In the third quarter of fiscal 2018, profits grew 70% from the year prior to $22.4 million. With shares quintupling from their low to end 2018 at $120 while worldwide stock markets were tumbling, RH investors who stayed the course have been handsomely rewarded. Friedman’s 10% stake is worth some $280 million. What’s more, he has options that, were he to exercise them, could raise his share of the company to 27%. RH’s improved financials appear to bolster his claim that its lavish new 90,000-square-foot store in Manhattan’s trendy meatpacking district represents the future of retail.

But a look under the couch cushions exposes questions about whether Friedman’s strategy of opening giant stores—which he calls “galleries”—is working all that well. Short-sellers, who hold 35% of RH’s outstanding shares, are also wondering how far Friedman will go to punish them by pushing the stock higher. Friedman says he isn’t distracted by the shorts. “We run the company like we own 100% of it,” he says.

Friedman’s critics say that financial maneuvers have artificially pumped up the stock and mask a flawed growth strategy. Between February and July 2017, the company used debt to buy back $1 billion of its own stock (50% of the company). Then in October 2018, with shares flagging from a June peak of $164, RH’s board approved another $700 million in share repurchases. Some also question Friedman’s incentives. In May 2017, two days before announcing a big chunk of the buybacks, the board okayed a pay plan in which he can purchase up to 1 million steeply discounted shares if the stock crosses $100, $125 or $150, at certain points between 2018 and 2021.

“These are complicated financials for what should not be a very complicated business, which is putting some crap in a store,” says Todd Fernandez, who runs Forensic Research Group, which has followed RH since 2014. “If the unit economics made sense, someone probably would have built stores like this.”

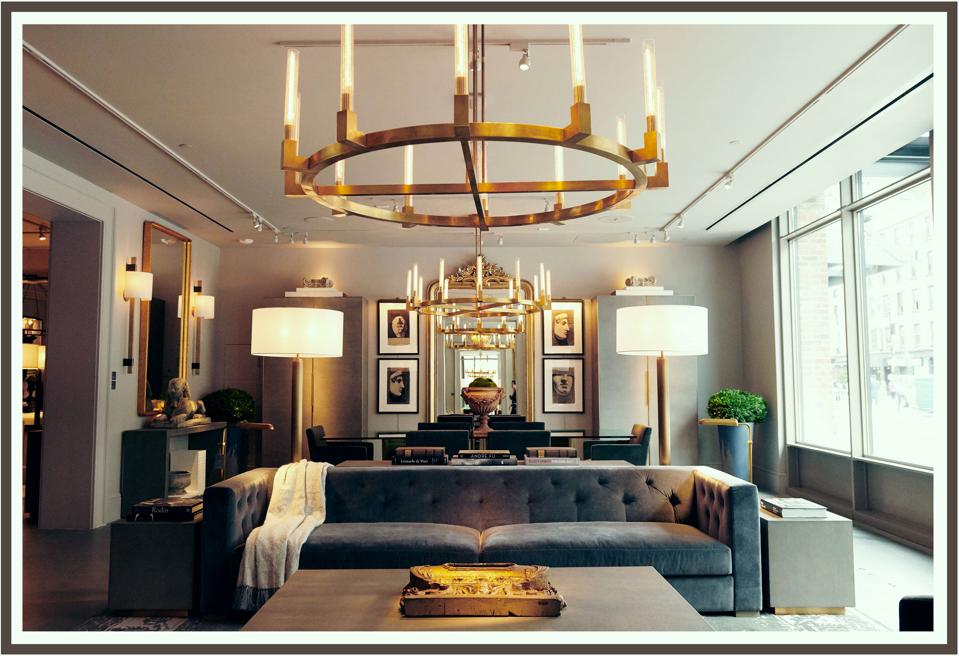

A display on the first floor of RH New York includes the Modena Tufted Shelter Arm Sofa, which starts at $4,695 for non-members, and chandeliers from the Cannele collection that can cost as much as $8,795.Jamel Toppin

Friedman insists that Wall Street misunderstands him, and certainly his background is different from that of the typical public company CEO. His father died when Gary was 5, and he was raised on welfare by his single mother, who battled schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. By his 18th birthday, the family had lived in 16 places, mostly in California. “We never had any furniture,” he says. He does remember one piece well: a coffee table his mother would dress up with Con-Tact paper. After dropping out of Santa Rosa Junior College, where he had a D average, he earned $2.10 an hour stocking shelves at The Gap.

After he was promoted to store manager, he caught the attention of Millard “Mickey” Drexler, the retail guru who was then remaking the chain. “Most people, if they’re talking to the president of the company, watch their words very carefully,” Drexler says. “Gary never watched his words. It was extremely helpful to know what he thought, without editing.” The two men remain friends and talk regularly, Drexler says.

By age 27 Friedman was overseeing 63 stores as a Southern California regional manager. He thought life couldn’t get any better, until 1988 when a recruiter offered him a chance to return north to run operations for Williams-Sonoma. The cookware chain doubled his salary and gave him a car allowance large enough to pay for a Porsche: “All the things you dreamed of when you’re a poor kid like me.” He eventually rose to president of the company.

In 2001, having been passed over for CEO, he left Williams-Sonoma for Restoration Hardware, which had been founded in 1979 by Stephen Gordon, who was renovating the Victorian home he and his wife had bought in Eureka, California, and started selling specialty hinges and doorknobs to people fixing up old houses. From there it grew to an everything store with more than 100 locations stocked with a quirky range of items with Baby Boomer appeal, from Mission furniture to mini Etch a Sketches. By the time Friedman signed on, Restoration Hardware was trading on the New York Stock Exchange with a measly $20 million market cap and was deep in debt, bleeding money but still opening stores.

Friedman overhauled the inventory and focused on contemporary furniture, lighting and bedding. He figured he could save the brand by leveraging the company’s favorable store locations and well-performing furniture business. But it proved a tough assignment. Friedman would ultimately spend $59 million (including most of his own savings) to keep the company out of bankruptcy. Then, in 2008, he teamed up with Catterton Partners, a private equity firm based in Greenwich, Connecticut, to take the company private for a reported $175 million.

CEO Gary Friedman’s favorite dishes at RH restaurants include a grilled cheese sandwich with truffle oil ($21 in New York) and warm chocolate chip cookies ($10).

To both supporters and detractors, the massive Manhattan store that opened in September embodies what Friedman has wrought from the old Restoration Hardware. The six-story space is three times as large as the previous New York City location in the Flatiron district. A central atrium allows visitors to gaze from floor to floor and showcases Friedman’s obsession with symmetry. On either side of the ground floor hang rows of identical crystal chandeliers that highlight seven-foot-tall replicas of 18th-century urns next to sofas upholstered in charcoal velvet.

The rooftop is dedicated to a 100-seat restaurant decked out with marble tabletops, London plane trees, Japanese boxwood hedges and yet more chandeliers. Chef Brendan Sodikoff, president of RH Hospitality and the creator of Chicago’s Au Cheval burger (ranked by one survey as the best burger in the nation), has designed a menu that includes $68 dover sole and an RH burger for $24. It’s the company’s fifth in-store restaurant and part of a growing hospitality division Friedman believes will entice patrons to live the RH lifestyle.

“We are moving from creating and selling products to conceptualizing and selling spaces,” he says. That includes RH Yountville in Napa Valley, a 9,000-square-foot compound that opened in December with a café, a stone wine-tasting vault, and two furniture showrooms. Next year, the first RH hotel will open around the corner from the New York store. Friedman says the New York restaurant is already operating at a $10 million annual run rate.

It was at Williams-Sonoma that Friedman began blowing up store size to boost sales. Inspired by the famous Harrods Food Hall in London, he expanded a shop from 2,500 to 5,000 square feet so that he could install a kitchen in the middle. Sales doubled.

Today Friedman points to large galleries as the key to making RH more profitable, forecasting in a June 2018 letter to shareholders that the real estate transformation will add up to 2% to RH’s margin in three years. (Hospitality is expected to add another 0.5%.) As brick-and-mortar struggles against e-commerce, Friedman argues, shifting online has been “unnatural” for many furniture brands. With RH’s locations averaging 17,000 square feet, he reasons, the company can display more of its massive inventory while paying less per square foot than when it mostly had mall slots half that size. The basement of the New York store is dedicated to lines for kids and teens—at first sold in a few stand-alone stores and online—like a $1,699 mini Kensington leather sofa.

“Why go into a store unless it is something that is going to wow you, stimulate your mind and senses? You can’t do that in a 1,000-foot store,” says Jared Epstein, principal at developer Aurora Capital Associates, which owns RH’s Manhattan space.

But critics argue that Friedman has a long history of overpromising—and his track record at RH includes a string of failed attempts at brand extensions. A 2013 New York art gallery couldn’t scale, a project promoting emerging musicians stalled out, and a luxury clothing line remains on the table.

In earnings calls, RH used to claim galleries in Beverly Hills and Houston were achieving more than $2,000 per square foot in annual sales. Today that would put the company behind only Apple and Tiffany’s, but RH no longer breaks out this stat at store level. Its 86 locations average $910 in sales per square foot, according to eMarketer. (At Ethan Allen, where sofa prices are several hundred dollars less than at RH, sales per square foot average $267.) Now Friedman says the goal of the larger stores is to grow volume, not earnings per square foot.

RH’s plan had been to open more than 10 galleries annually, but in 2018 it opened only four. The latest plan calls for opening up to seven 30,000-square-foot stores per year and testing a smaller format for minor markets. A three-year-old membership program that promises 25% off any purchase was supposed to eliminate the need for costly seasonal promotions, but in January the company was offering up to 70% off online and in stores. Despite all the emphasis on the brick-and-mortar experience, RH sells 42% of its inventory direct to consumers. And to environmentalists’ dismay, it continues to send out its glossy 300-plus-page catalogs.

In Glassdoor reviews, employees describe RH’s corporate culture as “cult”-like and leaders as “bullies” who act on impulse and play favorites. “We all answer to Lord Gary Friedman and the culture of this company is that we run like chickens with our heads cut off whenever he says anything,” wrote one employee in January 2018.

“We are not for the faint of heart. We are trying to be the best in the world,” responds Friedman. All employees get two pages of exhortations printed on heavy gray paper, which lay out “the Resto rules,” including “This is not our job, this is our life” and “We don’t believe in speed limits; We do believe that speed kills … the competition.”

A workaholic and a poor time manager, at our session in Corte Madera, slotted for three hours, Friedman talked for five. He can also be rambling and inarticulate in a way that borders on offensive, at one point comparing his effort to commission a piece of art for a stairwell in the Manhattan store to the work of Martin Luther King Jr. “All you gotta do is find other people that believe what you believe and you can create a movement,” he says. “It’s how most things work in the world. It’s the story, like Martin Luther King, right?” Today, stock analysts privately worry that Friedman’s weaknesses could hurt results, while simultaneously questioning whether the company would survive without him.

Not long ago that worry became a real possibility. As Restoration Hardware prepared to return to the public markets in 2012, Friedman, who was divorced, was pushed out as co-CEO over a relationship with an employee 30 years his junior. Friedman says he had a consensual relationship with a woman who had left RH and whose angry ex tried to create bad press for the company ahead of the IPO. This led him to temporarily give up the top job, but he was back nine months later. His co-CEO, Carlos Alberini, left to be chief executive of Lucky Brand in 2014 but still sits on the RH board, leaving Friedman as the top boss.

For now, Friedman is delivering with robust sales and a strong stock price in a down market. “A lot of people have lost a lot of money betting against Gary Friedman,” says Anthony Chukumba, an analyst at Loop Capital Markets. “If Gary is hit by a bus, sell the stock and look back later.”

Opening photograph by Jamel Toppin