Ground leases can provide great investment opportunities for people who want to deploy capital in real estate while never having to think about property management. The investor becomes the landlord under a long-term lease, often lasting 99 years. The tenant pays every conceivable cost related to the property and handles all management, and signs leases with space tenants who actually occupy space and do business or live in the building. The ground lease landlord collects rent that usually goes up over time.

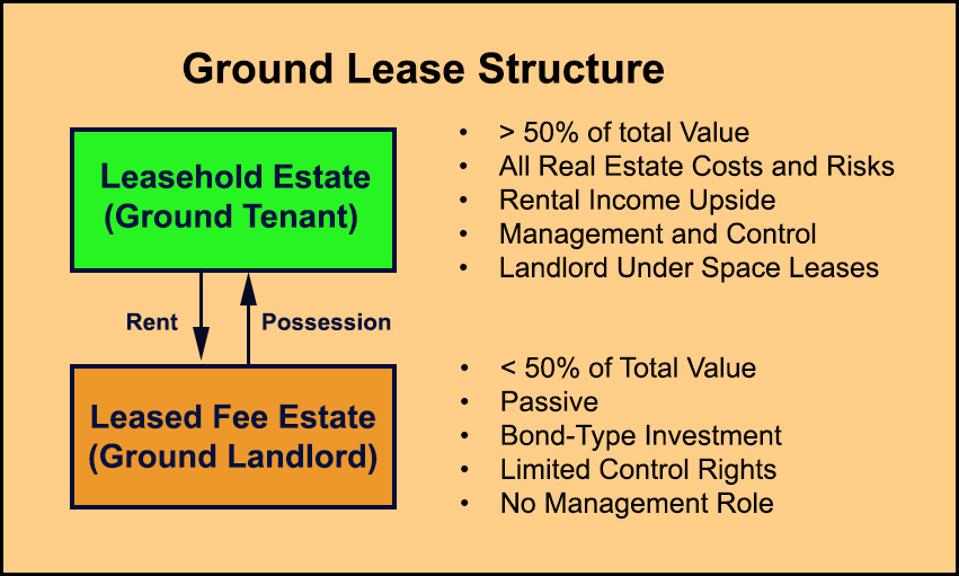

Under a typical ground lease, the lease covers raw land and the tenant then develops a building. The value of the rental stream and the landlord’s position will typically end up well below half the value of the land and building as a whole. The tenant’s position is quite valuable, so the tenant will probably pay the rent no matter what. The landlord effectively owns a bond, often at an attractive implied interest rate.

A ground lease creates two long-term interests in the same real property.

Ranjan Samarakone

Landlords under old ground leases rarely want to sell. So some real estate sponsors have gone into the business of creating new ground leases. The sponsor bifurcates an existing real estate asset into a leasehold (the tenant’s position) and a leased fee estate (landlord’s), and then finds an ideal owner for each. The total value of the two parts, each in the right hands, may exceed the value of the whole.

This technique is not new. Historically, though, ground leases created serious pitfalls for tenants, which led many real estate investors to categorically avoid buying the tenant’s leasehold position under any ground lease. Creators of modern ground leases try to avoid those pitfalls.

The largest and worst pitfall for tenants in ground leases has always related to future rent adjustments, a deal element driven by landlords’ fear of inflation. In response to that fear, many older ground leases say that every 20 or 30 years the rent will reset to equal 6% or 7% of the then-current value of whatever landlord brought to the transaction – typically vacant land but sometimes an existing old building. That made sense when real estate capitalization rates were 6% or higher. Today’s real estate values often reflect much lower cap rates, producing rent adjustments that can destroy the value of the tenant’s leasehold.

In response, modern ground lease negotiators often tie ground rent increases to inflation. The increases might occur annually, subject to a low percentage cap. They might also occur every few decades, again subject to a formulaic cap, such as 3% compounded annually. This helps protect tenants from the types of unpleasant surprises that have occurred at Lever House, the Chrysler Building, and other ground leased buildings in New York City. Landlords just have to live with the risk of hyperinflation if they want to sign modern ground leases.

Tenants also want to absolutely minimize the degree to which they ever need to go back to the landlord for anything. Any requirement for landlord approval creates the possibility that the landlord will disapprove. That would force the tenant to do something other than whatever the tenant thought made the most business sense. It might also require the tenant to write the landlord a check.

For example, any tenant will at some point probably want to sell its leasehold position. If the landlord has the right to approve the sale, even if the lease says the landlord must be reasonable, this could create a fight or a holdup opportunity. So a modern tenant will insist, and a modern landlord will often agree, that as long as the tenant has completed any contemplated development or construction work, the tenant can freely sell its leasehold to almost anyone. The lease may have a couple of objective and simple tests the purchaser must meet. Those tests will not involve any exercise of judgment or discretion by the landlord.

Similar dynamics arise for subleasing (the tenant’s leases with actual occupants of the building), construction work, financing, and a few other issues, such as potentially changing the use of the building, e.g., from an office building to a hotel. In each case, the tenant knows that any landlord approval right creates the potential for trouble, so the parties will agree instead on objective criteria and limitations that the tenant would need to satisfy in each case.

These and other measures can help a modern tenant create a flexible, stable, safe, and valuable leasehold estate that is almost like owning the property. As long as the lease also gives the landlord comfort that the building, the rental stream, and hence the landlord’s position will retain their value, the landlord can live with a modern ground lease too.